Fine Indigenous Forests

of the Garden Route

Indigenous forest - a self sustaining eco-system

Indigenous forest - a self sustaining eco-systemWe consider our indigenous forests to be a precious national treasure. They cover less than 1% of South Africa’s land area. Approximately 35800 ha of our temperate indigenous rain forest are state owned and are situated along the coastal belt between George and Storms River in the Western Cape, the region now known as the Garden Route.

There are 125 tree species found in these indigenous forests. The king is considered the Stinkwood -it has the most highly prized timber in the world, the Queen - the Yellowwoods; are the tallest trees in the forest, and the Ironwoods are the army, making up about 20% of the trees in the forest and a member of the large "Olive" family.

“Come walk with me, and we will see the forest green, touch its heart and sense its mystery”. Judith Hopley (On Foot in the Garden Route)

The History

These indigenous forests developed over hundreds of years because of the many rivers that flowed through the area and the high rainfall experienced in the region. They are described as “moist” and “medium moist” and consist of the tallest trees and most luxuriant undergrowth.

The well-known spectacular tree species grow in the wetter forests, for example the Stinkwood, Yellowwoods, Hard Pear, Ironwood and Cape Chestnut. White and Red Elder are found in wet river valleys and sheltered “kloofs”.

Other forest types are drier and rather scrubby and are found on the dry north and west facing slopes or along the windy coastal belt.

Although it has been widely expressed that exploitation reduced the indigenous forests enormously, the George area was the most affected. Apart from that, properly reviewed documentary evidence would indicate otherwise – that the area has been a mosaic of forest, fynbos, grassland, thicket and coastal (dune) forest for some hundreds of years.

For example, big herds of buffalo in fields are mentioned in some historical records, which would not have been possible if the area was all forest! Nor the grazing herds of antelope that roamed here!

And - Elephants numbered in their hundreds wandered freely over the whole terrain – fynbos, forest, grasslands, foothills, and beaches. The forest was not their natural habitat. They eventually retreated into it to escape relentless persecution by humans. Even then their existence was tenuous until after a final massacre in 1920 by a Major Pretorius who shot 7 in one hunt, there were less than 10 left. It was thought that the remnant would be unable to return from the brink of extinction………..but read Gareth Patterson’s amazing findings in his book, "The Secret Elephants”.

This is not to refute that uncontrolled woodcutting affected the indigneous forests adversely but that the destruction was much less than is frequently stated. On the contrary, cutting down big trees opened the forest canopy to allow sunlight to reach the ground and encourage saplings to grow, replacing harvested trees.

At other times in the region’s history, indigenous people’s habits of using the lower canopy woods and plants for their own needs affected the forests more seriously by degrading the primary undergrowth and reducing its ability to regenerate.

Farmers did not destroy forests to cultivate the land because these soils were notoriously poor and unsuited to agriculture. In modern times it is the dune forests along the coastline that are most threatened by human development.

Natural factors such as fire and on-going climate change i.e. less rainfall, drier soil conditions etc. have contributed to vegetation adaptations in this region. Some studies indicate that the relationship between fynbos and forest is a determining factor, that fynbos cannot invade forest but that forest can encroach on fynbos.

This is enabled by naturally occurring fires in fynbos that allow tree saplings to gain a foothold. This would indicate that indigenous forests have extended themselves in some areas rather than reduced.

Our Indigenous Forests Today

Sadly, the state of our indigenous Garden Route forests today is heartbreaking. The strict controls and policies that were in place to manage them (and that had set a world standard) have fallen by the wayside when it was decided that the management of these forests be handed over, in 2005, from the Department Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries to SANParks which fell under the Department of Environmental Affairs.

It took a while for SANParks to realise that harvesting the indigenous forests was costing them more than the income they were receiving from it. By 2010, they were losing up to R3million a year when the harvested woods went to auction. Under Forestry these losses were being absorbed, but this was not SANParks core business and they decided to outsource the harvesting to reduce their financial deficit.

This could have been an opportunity for SANParks to stand up as conservator of the forests and phase out the harvesting of these scarce and precious woods. Situated in the region known as an international tourist destination why did they not apply their minds to capitalising on environmentally friendly and educational activities?

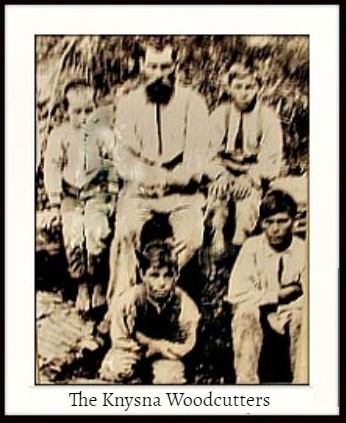

The inadequate recoupment for the harvesting of indigenous timber goes back to the days of the woodcutters who lived a hand-to-mouth existence because the timber merchants dictated what they would pay for the woodcutters' hard work. These men were forced to accept payment in the form of "good-fors" that compelled them to buy goods from stores owned by the timber merchants instead of being paid in cash. This held the forest people in a vicious cycle of poverty from which they had little opportunity of escaping.

In 1939 when the forests were closed to the woodcutters for good and the state department of Forestry had taken over responsibility for their management they also could not recoup their costs when the woods harvested went to auction but they made up for this indirectly by taxes levied on the processing aspects of the timber industry.

Instead, SANParks chose to put the harvesting process out to tender and awarded the concession to a BEE company, Kwakhanyisa Co-operative Ltd. The Co-operative had problems raisng funds to pay for the concession and in the end money came from a grant supplied by the Western Cape Provincial Government. Finally in December of the same year harvesting got underway. The company hired a competent sub-contractor, arborist Pieter Boshoff of Treepro, who had trained and qualified in America.

However, the company directors knew nothing about the important protocols involved in harvesting indigenous trees, their names, their individual commercial value or how to extract them without damaging the forest around them. Pieter fought an uphill battle to maintain harvesting protocols and conservation ethics but the odds were stacked against him. After four months he withdrew from the contract because the BEE company were in arrears with a large sum of money they hadn't paid Treepro for the work it had done.

So the formerly conservatively harvested and carefully chosen trees that were brought to specific depots for auction once a year in a major calendar event for both Forestry and furniture manufacturers came to an abrupt halt. It was timber that had been sold in log form by the cubic meter over a period of five days. Yellowwood, Stinkwood and Blackwood were the three most common species sold but small quantities of Ironwood, Hard Pear, White Elder and Candlewood and others had also been available for auction.

The fiasco that ensued destroyed the livelihood of many timber merchants and their workers in Knysna. In 2019, the concession that has left all parties involved with it, out-of-pocket with the forest itself bearing the brunt of gross mismanagement, has been halted. In the intervening years, invaluable knowledge and skills have been lost to the industry that are irreplaceable.

Indigenous Timber Auction held by Forestry

Indigenous Timber Auction held by ForestrySANPark's actions reflect a fundamental contradiction of their commitment to protect and conserve this precious natural resource which could have been creatively enhanced as an even greater tourist attraction than it already was. Resources: Forestry SA Magazine April and December 2013

This is even as the United Nations Environment Program states that Africa is suffering deforestation and forest degradation at twice the rate of the rest of the world. The Garden Route's small area of indigenous forest does not even rate as a percentage of the world's indigenous forests which is an indication of how rare it is and how much it's existence needs protection as part of all South Africans' natural heritage. In fact all harvesting of the Garden Route natural forest should stop! How these indigenous forests have been treated over the last 7 years since 2012 is a travesty that they will take decades to recover from, if ever, as we are fast reaching the tipping of being able to save the planet and all that live upon it, from the devastating, escalating effects of climate change.

In a few short years, the hope that the formation of the then new Garden Route National Park, now Biosphere Reserve, would allow different controlling bodies like SANParks, Environmental Affairs and the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, to jointly assess what was needed to correctly manage these natural resources, has died a painful death.

Colourful fungi on a dead Tree

Colourful fungi on a dead TreeIn 2014, the Knysna Timber Initiative, made up of local business people who have deep roots associated with the industry, was inaugurated in a valiant attempt to revive Knysna's invaluable historical heritage. They showcase their efforts through the Knysna Timber Festival that will take place in 2020 from 13-15 March.

Indigenous forests are critical mitigating elements of climate change. They absorb carbon dioxide, purify the air and release oxygen. Through respiration they release moisture into the air, that inevitably produces rain clouds. Worldwide these forests are being destroyed at a phenomenal rate and everywhere humanity is feeling the effect.

Indigenous forests are a plethora of interacting complex organisms, fauna and flora that are much more than the trees alone. Together they create a self-sustaining and regenerating ecosystem.

It is a wonderland of soft, tranquil beauty with an abundance of biodiversity unlike its man-made counterparts; single-species, fast-growing tree plantations such as pine and gums that do at least serve the purpose of taking the pressure off our precious slower growing indigenous woods.

However, the devastating wildfires of June 2017 and of October 2018 have had a far-reaching disastrous effect on plantation resources and their economy in the region and are having a hard-hitting effect on the local timber industry overall.

The Unique Character of Indigenous Forests

Man cannot recreate an indigenous forest because the factors involved to sustain such a venture are too complicated to duplicate.

A multitude of invertebrates such as insects, spiders, worms, snails and millipedes, amphibians such as the rain and southern ghost frogs and reptiles such as various snakes like the boomslang and puff adder inhabit every niche from the forest floor to the forest canopy in a complex ecosystem.

Projects that attempt to imitate it inevitably fail. The best most of us can do is plant indigenous trees suited to the area in which we live, in our gardens and public places and remove aliens which have become pests and compromise our fresh water supply. as they drain our rivers.

Indigenous forests have 5 distinct zones that can be identified as layers. From the ground upwards is firstly the herb layer, then the shrub layer, sub-canopy layer - young trees, the canopy layer - middle sized trees and the emergent layer - the trees that tower above the rest.

Together with the creatures of the forest the layers of vegetation create a self-contained ecosystem that constantly recycles its degrading elements so that nothing is wasted.

“Thank you God for quiet places far from life’s crowded ways, Where our hearts find true contentment and our souls fill up with praise!”

Links to Similar Sites

Mongabay.com was founded in 1999 by Rhett A. Butler. It has become one of the world's most popular environmental science and conservation news sites. The news and rainforests sections of the site are widely cited for information on tropical forests, conservation, and wildlife.

Rainforests provide homes and habitats for more than 50 percent of the species on Earth as well as for millions of Indigenous communities. What’s more, rainforests also serve as one of our key defenses against global warming by storing massive amounts of carbon. Over 40 percent of the world’s oxygen is produced from the rainforests. It may sound clichéd, but the adage is true: Rainforests are the lungs of the planet.

Carbon Tanzania works with local villages, community-based organizations, and rural extension and conservation organizations in Northern Tanzania. Together with those who demonstrate a commitment to sustainable, long-term forest management, equitable local benefit sharing and transparent governance, Carbon Tanzania aims to reduce the threats of global climate change by turning carbon dioxide emissions into natural Tanzania forests. Carbon Tanzania's projects not only contribute to conserving and protecting local ecosystems, but they also provide opportunities for improved local livelihoods.